Everyone, to one degree or another, has experienced anxiety at some moment in life. Whether it be butterflies in the stomach prior to speaking in front of a large group of people or the sense of quiet despair when you are demanded to do something you aren’t prepared for. Such moments are ubiquitous in cultures around the globe, and the common refrain is often to the tune of, “relax, don’t panic, and everything will be all right”. For some people, however, there is an existential certainty that everything will most definitely not be alright and, moreover, things may actually be extraordinarily, disastrously “wrong”. For such individuals, simple everyday tasks become painful ordeals overshadowed by a persistent sense of doom, misfortune or worse, impending death.

To the outsider, such people might look quite normal and are keeping their affairs in order remarkably well. But on the inside, there is nothing but chaos, frustration, worry, and despair – and for very good reason: most of them have been told by a medical professional that it’s “all in their head” and have been prescribed one or another of the insidious but wildly ineffective antidepressant or anti-anxiety medications that are in vogue in our time.

The truth of the matter is that anxiety – the type that is capable of undermining sanity and seriously disrupting quality of life – is a modern epidemic of much larger proportions than anyone would expect. In the US alone, nearly 20% of the population over the age of 18 has been formally diagnosed with an anxiety disorder1. That’s nearly 40 million people that have been documented. The numbers, in reality, are much higher, due to the fact that a large portion of the population is either in denial and accepting the condition as “part of their genetics” or too afraid or embarrassed to seek out help.

All it will take to convince yourself of this epidemic is to consider that Xanax, the most frequently prescribed drug for anxiety in the US, has seen a steady 9% rise in prescriptions since 2008. It is currently estimated that doctors write more than 50 million of these prescriptions per year, and the numbers are not declining. But as many that have walked this pharmaceutical path know too well, the deeper you go into a benzodiazapine addiction, the harder it is to crawl out of it.

Social media is rife with stories from ordinary people desperately seeking answers for a problem that medicine has only blanketed with drugs and psychotherapy. I frequently hear the common complaint that someone has “tried everything” and that their anxiety is treatment resistant. While there are some cases that may be solved by observing a cleaner diet and regular exercise, the majority of people I encounter are caught in a vortex of pain and disillusionment, having looked in all corners of the universe for an answer and coming up empty-handed with nothing but ever-increasing anxiety and despair.

So what’s really going on? Are people becoming more stressed out and overdriven as a result of the pace of our hyper-technological world, or are there other factors at play? That is the question we will explore in this article. What I hope to show you is that the situation is far more complex and multifacted than modern psychiatry presumes. Ultimately, if the most complex cases of anxiety disorder are to be sustainably resolved, they must be approached from a point of view that encompasses all relevant physiological, psychological, and environmental factors.

Far More than a Simple Diagnosis

At first glance, it might seem that the American Psychiatric Association has conclusively documented all potential manifestations of anxiety down to the last symptom and characteristic. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th edition, is so well formulated and laid out that it has become all but the only reference of choice for practicing psychiatrists and psychologists. What was under the general heading of “Anxiety Disorders” in DSM-4 has spawned three separate categories in DSM-5: Anxiety Disorders, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders, and Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders2. Reading the manual, one can easily become swayed into believing that anxiety is, in fact, quite cut and dried and one need only match a person’s behavior, symptoms, and familial history to the descriptions to derive a diagnosis. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

At first glance, it might seem that the American Psychiatric Association has conclusively documented all potential manifestations of anxiety down to the last symptom and characteristic. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th edition, is so well formulated and laid out that it has become all but the only reference of choice for practicing psychiatrists and psychologists. What was under the general heading of “Anxiety Disorders” in DSM-4 has spawned three separate categories in DSM-5: Anxiety Disorders, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders, and Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders2. Reading the manual, one can easily become swayed into believing that anxiety is, in fact, quite cut and dried and one need only match a person’s behavior, symptoms, and familial history to the descriptions to derive a diagnosis. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

In actuality, very few individuals that have subjected themselves to a practitioner of psychiatry or psychology that relies heavily on manuals such as DSM-5 to classify their ailments has come out the other end of the process with a permanent cure. Many of those patients, on the other hand, are painfully familiar with the doctor’s rhetoric – “you have a medical illness due to physiological, genetic, and biological influences and it can only be resolved with medicine and psychotherapy”. The patient is reassured that there is nothing morally or ethically “wrong” with them, but that they were simply dealt some bad cards in the game of life and must do what they can to support their weaknesses. Unfortunately, analysis of symptoms, behavior, familial history, and life traumas is not sufficient to truly understand what makes a person tick. As a matter of fact, it doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface.

When we examine the descriptions of the most common anxiety disorders, it is clear that the primary focus has been on what is occurring physiologically and psychologically with little to no consideration for the multitude of potential root causes.

For example, panic disorder is described as a pathology that begins with a sudden attack accompanied by symptoms such as palpitations, shortness of breath, tightness in the chest, gastrointestinal distress, sweating, and hot / cold flashes. The first incident is never expected and often reported to feel like one is either losing one’s mind or on the verge of death. There could be multiple physical or psychological triggers for this attack, but the initial onset is followed by months or even years of chronic worry over the possibility of a repeat experience. The worry, in turn, often invokes the symptoms that produce subsequent attacks, perpetuating a vicious cycle.

Modern psychiatry retells the story of panic disorder quite well, but explanations for why it is happening are sparse and vague at best. The usual suspects are genetic mutations, life traumas, or the existence of other serious conditions such as depression, alcoholism, or drug abuse. We often hear such statements as “panic disorder is a serious condition that strikes without reason or warning.”3. Such statements are unassumingly deceptive. In nature, there are always reasons and, if you know where to look, frequent warnings. Simply because they are not obvious to science is in no way an indication that they do not exist. But before we launch into a discussion of the root causes and triggers, we should divert our attention momentarily to another seemingly simple question:

What differentiates a person with anxiety disorder from a normal, level-headed, resilient human being?

The Fine Line Between Sanity and Illness

It’s tempting to think that a person suffering from anxiety is, intrinsically, the result of one or more weaknesses to which he / she has succumbed due to environmental pressures. Our society subconsciously accepts this explanation along with the pharmaceutical and therapeutic aids prescribed to address those weaknesses. What we commonly fail to see is — deep in the recesses of that very subconscious is a hidden belief that some people may simply be born with natural strength and resilience. This isn’t a hard truth but rather a silent presumption, especially in the minds of those afflicted with the symptoms of a mental disorder.

It’s tempting to think that a person suffering from anxiety is, intrinsically, the result of one or more weaknesses to which he / she has succumbed due to environmental pressures. Our society subconsciously accepts this explanation along with the pharmaceutical and therapeutic aids prescribed to address those weaknesses. What we commonly fail to see is — deep in the recesses of that very subconscious is a hidden belief that some people may simply be born with natural strength and resilience. This isn’t a hard truth but rather a silent presumption, especially in the minds of those afflicted with the symptoms of a mental disorder.

The very word “disorder” harbors within it overtones of chaos and despair. It is all too common to hear someone with anxiety disorder expressing their frustration that “others can take life with stride while I, in my weakness, am unable to even cross the street without panicking”. Self-deprecation and a sense of inadequacy are common. What may not be so clear, even to a skilled mental health professional, is that any person, regardless of their apparently pristine genes, exemplary upbringing, or prudent life choices, may collapse into an unforgiving anxiety disorder, given the perfect storm of biological and environmental triggers.

Over the years, the medical community has made several postulations about the characteristics that separate sanity from mental illness. Research in clinical neurobiology has historically focused on dysfunction in neural circuits and neurochemistry, genes that confer vulnerability, and psychopharmacology. Up until the early 2000’s, little to no discussion was made about the neurobiological characteristics that afford protection against anxiety disorders. Some mental health professionals, however, began asking the right questions around that time.

One article, in particular, published in Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience by Dennis S. Charney (Sep. 2003 – Vol 5, No.3), discusses at length the psychobiology of resilience and vulnerability to anxiety disorders. A compelling consideration was made of the role that neurochemicals, neuropeptides, and hormones play in the regulation of resilience to stress. Charney posited that chronic exposure to stress in any form, from early childhood to adulthood, could potentially create significant changes in neurochemical and neurohormone function. Resulting imbalances could then lead to the establishment of long-term neural circuits conditioned to less sense of reward, greater fear, and aberrations in social behavior.

But what about the individuals that suffer from acute anxiety that have never experienced a traumatic event during their life? Is it possible that they, too, are the subject of neurobiological imbalances and inadequate neural imprinting? Yes, absolutely! As I will elaborate in great detail below, there are multiple roads that lead to the psychobiology of anxiety, many of which have very little to do with external stress. The truth of the matter is that the line between sanity and illness may be considerably thinner than society presumes, and the perfect storm can begin with the most meager changes in the internal landscape of the human body.

All people that suffer from anxiety, regardless of whether or not they have received a formal diagnosis, have several key factors in common. In order to mitigate or, preferably, completely reverse the pathology of anxiety, it is important that we not get trapped in tunnel-vision, as many mental health practitioners are so inclined to do. As you will see, it is not enough to know that you may have imbalances in neurotransmitter or hormone functions, nor is a full acknowledgement of your past traumas going to pull you completely out of the darkness. If anxiety is going to be banished once and for all, we must take an exhaustively comprehensive approach that not only combines the best of all methodologies but goes beyond them to a completely new paradigm.

If you haven’t uncovered and deeply understood all the factors that comprise human consciousness, you will forever be vulnerable to a recurrence of the pathology of anxiety. While it may be enough to temporarily find relief with a single approach, the hidden areas – the subclinical, unacknowledged psychological and physiological factors – will always be in line waiting for the right time to attack. And when they do, it doesn’t matter how well put together you are. All it takes is but one leg to fall before the entire table follows.

A Unified Perspective on the Causes of Anxiety

In order to understand the true causes of a given individual’s anxiety disorder, it is of paramount importance to appreciate the factors that make that person unique. Nonetheless, in dealing with a wide array of clients over the years with varying degrees of disorder, I have seen distinct patterns emerge that are common among all cases. Therefore, before embarking on a radically customized protocol that takes into account all the minor details of the client’s case, we must first be certain that all of these common patterns have been considered, in great depth. This ensures that we do not miss any important clues that could help uncover critical root causes for the pathology.

In order to understand the true causes of a given individual’s anxiety disorder, it is of paramount importance to appreciate the factors that make that person unique. Nonetheless, in dealing with a wide array of clients over the years with varying degrees of disorder, I have seen distinct patterns emerge that are common among all cases. Therefore, before embarking on a radically customized protocol that takes into account all the minor details of the client’s case, we must first be certain that all of these common patterns have been considered, in great depth. This ensures that we do not miss any important clues that could help uncover critical root causes for the pathology.

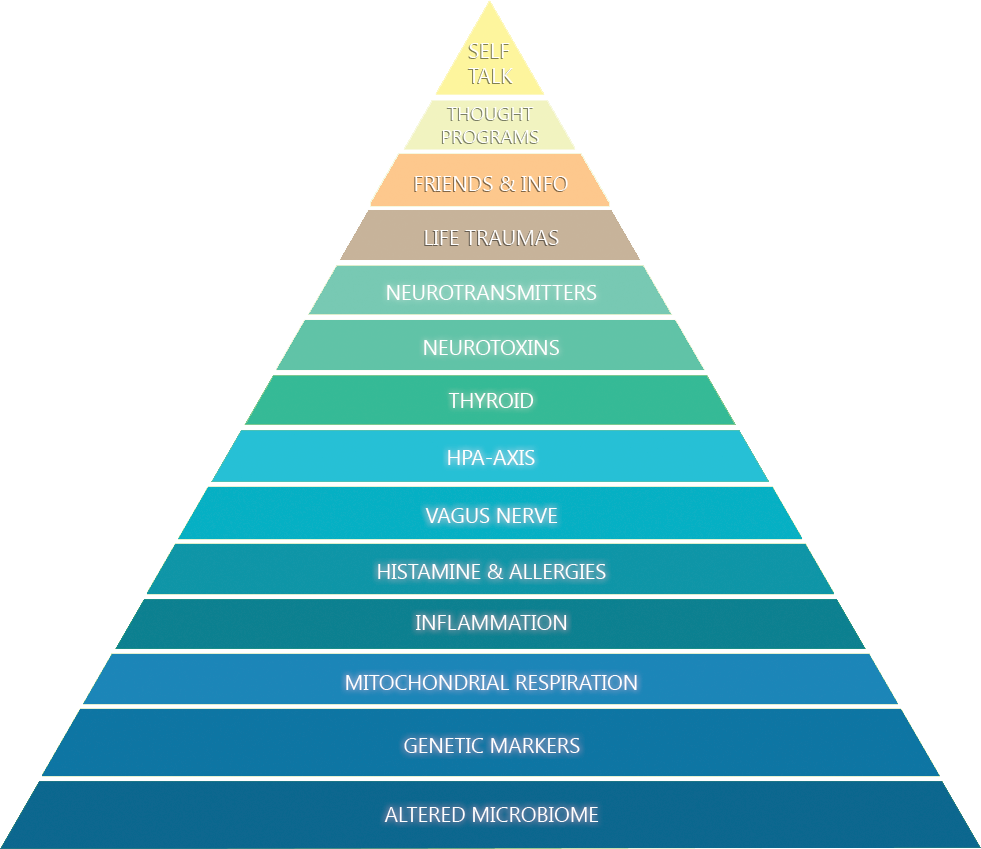

Rarely do I encounter a person that does not have major issues in at least 3 or 4 of these core areas. Many have lived their lives suffering with symptoms in nearly all of them. The problem, I have found, lies less in the skill of the clinicians or mental health practitioners one has consulted and more in a lack of thoroughness to leave no rock unturned. For this reason, I have designed a pyramid that conveys a unified perspective for discovering the root causes of anxiety.

Issues of greater priority comprise the base of the pyramid culminating higher up in the area where most mental health professionals begin – neurotransmitter imbalances and psychological patterning. This is not to say that the areas toward the top of the pyramid are not equally as important, but they do tend to present in parallel with issues farther down in the hierarchy. In any case, as you will see, the roots of anxiety are most certainly not only in the head but rather deeply embedded in the body as well.

The Anxiety Pyramid

Physiological Factors

Altered microbiome

Does it surprise you to find that the microbiome is at the deepest level of all anxiety pathologies? If so, read on. The human microbiome is the ecological community of commensal, symbiotic and pathogenic microorganisms living in nearly every part of the human body, including the skin, gut, and inside of the nose. It is now estimated that humans are 90% microbial and only 10% human! This should provoke a very deep consideration in you.

What we believe ourselves to be is not as concrete and distinct as we have thought all along. In truth, the human body is not a single organism but an entire ecosystem consisting of trillions of microorganisms that outnumber human cells by 10 to 1. Due to their size, they comprise only 1 to 3% of the body’s total mass, but their function and effect on nearly every process in the body is absolutely staggering. Truly, we could not survive without this ecosystem, as it has evolved symbiotically with human cells and provides critical support, not the least of which is digesting food and producing neurotransmitters.

In 2008, the US National Institute of Health launched the $115 million dollar Human Microbiome Project. It’s objective was to characterize microorganisms found in both healthy and diseased humans. Lasting for more than five years, this project opened the door to studies which would, in time, link human health and disease to the microbiota in the human gut.4

The majority of information today connecting the microbiome to disease is less than a decade old, and many (if not most) of the mental health clinicians are either not aware of the studies or have not kept up to speed with research. This is evident from the increasing number of anxiolytic pharmaceuticals that continue to be prescribed by psychiatrists around the globe, despite rising incidence of dependency and other dangerous side effects. For this reason, it is unlikely that your average clinician will look first to your microbial populations to gauge the root causes of mental distress.

Nonetheless, evidence is mounting that would prove the critical role that commensal, probiotic, and pathogenic bacteria play in the gastrointestinal tract by activating neural pathways and central nervous system signaling systems.5

Of particular interest to the anxiety patient should be the studies showing how gut bacteria produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA. These are the main players in mood regulation and many antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs manipulate them in one way or another.6 As a matter of fact, it is estimated that 90% of serotonin, the inhibitory “feel-good” neurotransmitter, is produced exclusively in the digestive tract.7 Further, some gut microbiota have been shown to actually control tryptophan metabolism along the kynurenine pathway, potentially reducing available serotonin and increasing neuroactive metabolites – metabolites which have been implicated in diseases such as unipolar depression, bipolar manic-depressive disorder and even schizophrenia.8

Pathogens such as parasites and gram-negative bacteria, if given the opportunity to proliferate in the gut, have been shown to hijack neurotransmission and hormonal communication. In some cases, they were observed to interfere with the neurons and brain regions that mediate behavioral expression.9

Some bacteria, such as Pseudomonas, Citrobacter, Aeromonas, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli also produce toxic gases like hydrogen sulfide which can induce disturbing symptoms such as fatigue, loss of appetite, headaches, irritability, poor memory, and dizziness. At levels as low as 10-50 ppm, nausea, vomiting, and difficulty breathing may be seen.10

Clearly, the microbiome is more than an ecosystem of microorganisms that extends the human body. It comprises the majority of our DNA and losing even small populations due to use of antibiotics or alcohol / drug abuse can have devastating effects not only on our overall health but our psychological disposition as well. It could even be said that the microbiome is a unique, whole-body “fingerprint” that directly influences who we are as human beings, both physically and psychologically.

For this reason, we must look first to disturbances in the microbiome to understand, in very concrete terms, what is at the root of mental and physical disturbances.

Genetic markers

Next in line is an area in which many clinicians easily get stuck. It is often suggested, in the mood of pre-determinism, that the genes we inherit from our parents and their predecessors, across multiple generations, can increase our liability for succumbing to mental illness. Sigmund Freud was known to label this as the “hereditary taint”, drawing from the then fresh work of the Austrian geneticist, Gregor Mendel.

In reality, inheritance is not as simple as Mendelian genetics might infer. In order to truly understand how genes influence our body and mind, we must look to the science of epigenetics, which concerns itself with the study of variations in cellular and physiological traits – in other words, how gene expression is altered by external or environmental factors. These factors switch genes on and off and effect how cells function. The first step in understanding your unique biology is by studying the “template” from which your body and brain have developed. Some conditions are inherited and have a higher likelihood for expression. This is seen as a prevalence of certain symptoms in your direct family line. The majority of chronic illness, mental or physical, however, is the result of various environmental influences since birth that have dynamically altered the transcriptional potential of your cells. That said, by knowing where the “weak links” are in your template, we can ask better questions and make more accurate assumptions about the origins of your symptoms.

Many gene interpretation services in the field make the mistake of correlating the presence of polyphorphisms (i.e. mutations) with risk for illness or disease. They often recommend solutions that involve supplementation and changes to diet. I do not and will not support this paradigm. A gene record could show mutations in spades for everything from heart disease to schizophrenia, but the patient may not present with any symptoms at all and live a full, healthy life, completely disease free. The fact of the matter is that any number of environmental influences such as heavy metals, pesticides, diesel exhaust, tobacco smoke, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, hormones, radioactivity, viruses, bacteria, and even stress can effect gene expression. We shoud, therefore, look first to a person’s history of exposure to these influences to better understand symptoms.

Nonetheless, I believe that knowing your basic “DNA template” will give you the tools you need to gauge epigenetic activation of certain genetic traits. For example, if we see in your genetic record that there are absolutely no polymorphisms in the genes that control neurological serotonin transport and release, it would be wise not to focus energy on strategies that manipulate serotonin levels. We will look elsewhere.

That said, I will list a few of the top genes I consider when analyzing the pathology of anxiety disorder. Knowing whether or not you have polymorphisms in these genes can be immensely helpful in understanding the idiosyncrasies of your condition.

HTR1A – also known as the 5-HT1A receptor, HTR1A is a subtype of the 5-HT (serotonin) receptor. It is responsible for decreasing blood pressure and heart rate and inducing the secretion of feel good hormones such as oxytocin and beta-endorphin. Disruption of this receptor’s function can result in perturbations in the serotonergic regulation of emotional state.11

GAD1 – Glutamate decarboxylase is responsible for catalyzing the production of GABA from L-glutamic acid. GABA is the primary neurotransmitter associated with reducing neuronal excitability throughout the nervous system. Its receptors are the targets of the majority of most popular anti-anxiety medications such as Xanax and Ativan. In the presence of mutations in GAD1, there can be potentially less GABA and more glutamate in the brain leading to a heightened risk for overexcitability and anxiety. GAD1 gene polymorphisms have been linked in multiple studies with anxiety disorders, major depression, and neuroticism.12

SLC6A4 – the serotonin transporter (SERT or 5-HTT) is responsible for transporting serotonin from the synaptic cleft to the presynaptic neuron. Without a fully functional transporter, serotonin’s effect can be significantly diminished, even in the presence of higher levels of the neurotransmitter. Polymorphisms in this gene have been correlated with a greater tendency to neuroticism. One analysis revealed a positive linkage between SLC6A4 and the anxiety-related behaviors of anticipatory worry and fear of uncertainty.13

COMT – Catechol-O-methyltransferase degrades dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, also known as catecholamines. Polymorphisms in this gene can result in lower levels of COMT. This leads to higher stimulation from catecholamines and a stronger tendency to develop phobic anxiety.14 Further, when catecholamines are elevated in the brain, in particular the hypothalamus, it has been shown to induce secretion of CRH (corticotropin-releasing hormone), a key peptide involved in stress response, fear, and anxiety.15

DRD2 – D2 subtype of the dopamine receptor is responsible for inhibiting adenylyl cyclase. It is involved in the mediation of reward pathways in the brain and has been the subject of multiple studies on addictive behavior.16 This receptor has further been implicated in depression, anxiety and social dysfunction in veterans with PTSD.17

MME – membrane metalloendopeptidase is one of the major enzymes known for its role in the degradation of enkephalins. Enkephalins have been shown to regulate mood, anxiety, reward, euphoria and pain. Variations in enkephalin metabolism have been clinically correlated with phobic anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder.18

PLXNA2 – the plexin-A family of semaphorin co-receptors participate in the process of nervous system development early in life. Polymorphisms in this gene have been linked to reductions in adult neurogenesis (i.e. inhibited creation of new neurons in the brain) and the development of anxiety, depression, neuroticism, and psychological distress.19

RGS2 – regulator of G-protein signaling 2 is a protein that controls signaling through G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR). These receptors are involved in a wide array of physiological functions including regulation of mood via serotonin, dopamine, GABA and glutamate. Defects in RGS2 expression been associated the introverted aspects of anxiety disorder as well as elevated activity in the insular cortex and amygdala. The amygdala, in particular, is responsible for the regulation of autonomic responses associated with fear.20 It has been shown that children suffering from anxiety have a larger amygdala21, and genes such as RGS2 could play a role in the development of such pathologies.

SLC6A3 – the dopamine transporter is responsible for pumping dopamine out of the synapse back into cytosol, where it is stored for later release. In the presence of polymorphisms in this gene, it is possible for synaptic dopamine levels to increase causing potential overexcitation and, in severe cases, schizophrenia.

There are far more genes that could play a role in the pathology of anxiety disorder than are listed here. All of them are included in our comprehensive gene analysis as part of the Transcend Genomics program, in addition to thousands of other key genes in all major human organismal and metabolic pathways. As stated above, our approach to using genes as a diagnostic tool is less based in classic determinism and more in the science of epigenetics. Having polymorphisms in any of the genes listed above does not guarantee their expression nor the disruption of mental or physical health. They are merely indicators that may be useful in describing the origins of pre-existing symptoms. Nothing more, nothing less.

Mitochondrial respiration

Mitochondria are organelles found in every cell in the human body except red blood cells. They break down and convert the nutrients found in food molecules to create ATP, the universal energy donor. They do this via a process known as cellular respiration or oxidative phosphorylation. Damage to the mitochondria has been implicated in a wide range of diseases including autism, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, and bipolar disorder. Of particular interest to us is the unassuming role mitochondria play in the pathology of anxiety disorder.

Mitochondrial respiration generates energy by transferring electrons across its inner membrane. This process is referred to as the electron transport chain. Complexes I and III in this chain are known to be potent producers of cellular superoxide, a reactive compound that causes oxidative stress and damage in cell structures like lipids, membranes, protein and DNA. In a healthy, young person, there are adequate defense mechanisms in place to neutralize this compound, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase. Adequate dietary supply of antioxidants such as vitamins A, C, E, and selenium also powerfully lowers oxidative stress. The older a person is and the more compromised these defense mechanisms are (regardless of age), the greater the accumulation of superoxide and resulting cellular damage. As this cascade of damage proceeds, energy levels drop due to lower ATP output and psychological disorders such as anxiety can develop.22

It is, therefore, very important to consider one’s genetic profile for antioxidant defense as well as biomarkers for oxidative stress to determine if they are a factor in the anxiety pathology.

Inflammation

Moving up the pyramid from mitochondrial respiration, we come to inflammation. One of the most potent triggers for whole-body inflammatory response is high levels of oxidative stress. We have already discussed how mitochondrial respiration can contribute to this burden with the production of superoxide without adequate antioxidant defenses, but what may not be so obvious is how a disrupted gut microbiome can also throw oil onto that fire.

Inflammation, in a healthy individual, is a normal response to biological insults from pathogens, cell and tissue damage, and irritation. It is typically experienced as redness, swelling, heat, pain and internally as aches in various areas of the body. However, if the gut microbiome has been disturbed and there are an unhealthy level of pathogenic bacteria, this can lower IgA levels in the mucosal lining, increase intestinal permeability, and induce a chain reaction of unrelenting, chronic inflammation in not only the body but the brain as well.

When the intestines are more permeable, larger molecules are allowed to leave the gut and enter circulation. This can include food proteins, bacteria, viruses, and parasites. When the immune system senses the infiltration of these molecules into the bloodstream, it up-regulates pro-inflammatory molecules such as cytokines to deal with the problem. In particular, elevations in the levels of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta), and interleukin 6 (IL-6), all pro-inflammatory cytokines, have been shown to increase psychological stress and stress-induced anxiety.23

Over time, if the problems in the gut are not addressed, the “cytokine storm” can further intensify. Cytokines are able to directly and rapidly cross the blood-brain barrier, and if the storm is not mitigated, that barrier will eventually wear down, causing an inflammatory cascade within the brain itself. High IL-1 levels in the brain, in particular, have been linked to panic disorder24.

Histamine and allergies

Next in line we have histamine. Histamine is primarily known for the role it plays in immune response to foreign particles such as pollens, mold, dust, mites, and pet dander in the nasal mucous membrane. By inducing vasodilation and increased vascular permeability, fluid is released from capillaries into tissues producing a runny nose and watery eyes. But this is not the only function histamine serves in the body. In reality, its role is far more complex, regulating a wide variety of functions such as blood pressure, sleep-wake cycle, and gastric acid release.

Though most histamine in the body is generated in mast cells, basophils and eosinophils (i.e. white blood cells). It can also be found in brain tissues, where it serves as a neurotransmitter. Histamine H3 receptors, in particular, found in the central and peripheral nervous systems, play a significant role in the regulation of acetylcholine, norepinephrine, and serotonin, indicating histamine’s ability to regulate mood and cognition.

Histamine can become a rather large problem when its accumulation far exceeds the body’s ability to degrade it. There are several mechanisms by which this may occur, not the least of which is a pre-existing inflammatory cascade. As we have already discussed, inflammatory response throughout the body can be hyperactive due to an altered microbiome and resulting intestinal permeability. As pathogenic endotoxins enter the blood stream, mast cells throughout the body destabilize and release a mixture of compounds including histamine, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes, all part of the pro-inflammatory immune response.

To add insult to injury, in parallel with mast cell release of histamine, there may be a compromised ability to degrade histamine contained in common foods due to genetically lower levels of diamine oxidase (DAO). When eating foods such as cured or leftover meats, canned seafood, wine, and all fermented foods (e.g. sauerkraut, soy sauce, vinegar, and yogurt), total histamine levels will rise even further, creating a potential crisis. Symptoms may include sudden drops in blood pressure due to histamine’s vasodilating properties followed by palpitations as the heart speeds up to pump more blood throughout the body. In some cases, there may even be severe shortness of breath from bronchoconstriction, arrhythmia, and flushing, further increasing a sense of existential urgency.25 As a result, histamine can become a powerful trigger for panic disorder.

Vagus nerve

As we move further up the pyramid, physiological anxiety may already be well established due to neurochemical and hormonal imbalances, epigenetically activated polymorphisms, oxidative stress, runaway inflammation, and high histamine levels. As a result, several changes in physiological function may begin to surface including shallow breathing, slower recovery from exercise, and a gradual decline of key neuropeptides and neurotransmitters, including oxytocin and serotonin. This will eventually lead to the “atrophy” of the vagus nerve, sometimes called low vagal tone.

The vagus nerve is part of the parasympathetic nervous system which is responsible for rest and digest functions. It is the longest nerve in the human body, extending from the cranium, through the neck, chest, and abdomen and all the way down into the colon. This nerve further commands parasympathetic control over the heart, lungs, and digestive tract, making it a key to understanding the physiobiology of anxiety disorder.

When the vagus nerve loses its tone, there is lower parasympathetic nervous activity which leads to less inhibition of the fight-or-flight sympathetic nervous response. As a result, mild environmental stimuli will have a greater ability to startle or cause psychological destabilization. Without the counterbalance and calming influence of the parasympathetic response, due to an underactive vagus nerve, any perceived tension or stress internally or in the environment will have the ability to trigger increased heart rate and blood pressure, dry mouth, adrenaline spikes, and the resulting cascade of physiological and psychological disturbances that define a panic attack.

In other words, disruption of vagus nerve function in any form leads to a potentially chronic state of physical and mental stress. This can be as inconsequential as occasional background anxiety or as serious as debilitating panic, depending on the severity of dysregulation.

HPA-Axis

As vagus nerve tone declines and inflammatory response continues to run rampant, neuroendocrine function also begins to go off a cliff. Perhaps the most influential neuroendocrine system in the human body is the HPA-Axis, consisting of the hypothalamus, pituitary and adrenal glands. In a complex exchange of hormonal messages, these organs control our reactions to stress and regulate key processes such as digestion, immune response, and energy storage and expenditure.

Stress, physical exertion, inflammation, and illness will all cause the hypothalamus to release corticotropin-stimulating hormone (CRH), which in turn stimulates the posterior pituitary gland to produce adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH is then transported via the blood to the adrenal cortex of the adrenal gland where it further stimulates the biosynthesis of cortisol. Cortisol, of course, is the major steroid hormone responsible for the regulation of stress response, blood sugar, and inflammation.

When the CRH-ACTH pathway is disrupted in any way, this can lead to a chronic stress response and elevated cortisol levels. This is especially true in the presence of chronic inflammation. If the stress response is unabated, that increased cortisol will eventually suppress immune function and disrupt circadian rhythm, resulting in further dysregulation of neurochemical and neuroendocrine function. This is part of the reason why people with chronic anxiety are prone to insomnia and additional comorbid mood disorders.

Over time, if this chronic neuroendocrine dysregulation is not addressed, additional problems will begin to surface. Elevated cortisol will continue to wreak havoc by chronically raising blood glucose levels leading to spikes in insulin. This spike will cause blood sugar to suddenly drop, inducing an “emergency response” from the adrenals to produce adrenaline. Though adrenaline does stimulate the liver to convert glycogen to glucose, via gluconeogenesis, it also has peripheral effects on the muscles and heart, producing anxiety and panic. At this point, glucose sensing neurons in the hypothalamus will signal the need for additional release of CRH, starting the vicious cortisol-glucose-insulin cycle all over again.

Thyroid

As the HPA-axis moves into a state of further array, the thyroid is not far behind. The thyroid produces the iodine-containing hormone T4 (thyroxine) which is converted to T3 (triiodothyronine) both directly in the thyroid and in the liver, gut, skeletal muscle, and brain. T3 increases basal metabolic rate, increasing the body’s consumption of oxygen and energy. Adequate T3 levels are absolutely mandatory for survival, and altered levels cause widespread disruptions to nutrient absorption, fat degradation, rate and strength of the heartbeat, mitochondrial respiration, body temperature, and more.

Thyroid hormones are produced via a cascade of signals starting in the hypothalamus, which pulses thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) when it senses low T3 / T4 levels. TRH, in turn, stimulates the pituitary gland to release thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) which induces production of T4 in the thyroid. If there are any disruptions in the HPA-axis as described in the previous section, thyroid dysfunction can quickly ensue. Cortisol, in particular, inhibits the conversion of T4 to T3 and effectively decreases TSH. This leads to lower thyroid hormone output and the symptoms of hypothyroidism.

Though anxiety is not typically correlated with hypothyroidism, a compelling connection does exist. Some studies have suggested that low thyroid hormone levels can increase turnover of serotonin, thus increasing sympathetic nervous activity.26 If there are already lowered levels of the inhibitory neurotransmitters serotonin and GABA, low thyroid hormones could easily exacerbate the problem, driving the body and brain in a more chronic fight-or-flight reflex in the presence of stressful stimuli.

On the other side of the spectrum, too much thyroid, as is seen in hyperthyroidism, can easily induce symptoms of acute anxiety due to a sharp rise in metabolic rate. Symptoms include abnormal heart rhythm, palpitations, mood swings and panic attacks. Further, it has been proposed that T3 and its metabolites serve as cotransmitters with norepinephrine, the precusor to adrenaline, in the sympathetic nervous system.27

It is therefore necessary to perform a comprehensive thyroid panel, including thyroglobulin and thyroid-peroxidase antibodies, in the presence of anxiety disorder, especially is there are comorbid issues with the HPA-axis.

Neurotoxins

Moving toward the top of the physiological portion of the pyramid, we see a wide variety of poisonous substances, both in nature and chemically engineered. These neurotoxins have the capability of destroying nerve tissue in both the central and peripheral nervous systems. They either interfere with communication between neurons at synapses or disable control mechanisms that regulate ion concentrations across cell membranes.

Exposure to neurotoxins in modern society is a growing problem, not only due to increasing levels of pollutants being ejected into the atmosphere and into our waters, but also as a result of non-organic materials used throughout our living and working environments. Once all the areas below this level in the “anxiety pyramid” have been tested and addressed, if necessary, it will be important to consider the presence of neurotoxic loads in the body and how they might be contributing to anxiety disorder.

Various symptoms may be present, depending on the type of toxin. Some of the most common are cognitive impairment, emotional chaos, panic attacks, paranoia, and even schizoid personality disorder. Mental health practitioners commonly overlook the possibility of neurotoxicity as a contributing factor to anxiety disorder and prescribe medication that, in some cases, may even increase overall toxic burden and exacerbate the symptoms.

A list of all existing neurotoxins and their effects could easily fill several volumes, so we will focus on a few examples:

Lead – a highly poisonous metal present in high concentrations through the burning of fossil fuels, mining, and manufacturing. The potential for water contamination is elevated in locations close to mines, industrial plants, and waste dumps. It may also be present in cheap ceramics and porcelain, which can leach into food, and children’s products made of vinyl or plastic. People with high blood lead levels have been shown to be 4.9 times as likely to suffer from panic disorder.28

Mercury – environmental levels of this metal are elevated near hydroelectric, mining, pulp, and paper industries. It can make its way into bodies of water such as lakes and streams where the microorganisms convert it to methylmercury. This form of mercury may be found at its highest levels in longer-living predator fish such as shark, swordfish, king mackerel, albacore tuna, and tilefish. Methylmercury has the potential to increase intracellular concentrations of calcium ions around neurons29. Excitatory neurotransmitters such as glutamate can facilitate excessive calcium ion influx, inducing excitotoxicity and severe anxiety.

Benzene – this organic chemical is a natural constituent of crude oil, but can also be found in a surprisingly large number of everyday products such as paint, glues, furniture wax, detergents, inks, and rubbers. High exposures are also linked to dry cleaning and motor vehicle exhaust. Multiple studies have demonstrated a link between benzene-containing solvent exposure and anxiety disorders with PTSD-like symptoms.30

Neurotransmitter / receptor impairments

Modern psychiatry typically begins at this level. Though some attention is often placed on genetics, it is peripheral at best, frequently accompanied by the presumption that mental disorders are possibly hereditary. The main tenet among modern clinicians is that anxiety is primarily the result of “neurochemical imbalances”. This should be glaringly obvious from the rising number of pharmaceutical prescriptions worldwide, such as Xanax, Ativan, and Valium. The clinician will tell you that “though life trauma and other sources of stress could have played a role in triggering a manifestation of the problem, you were born with neurochemistry that makes anxiety a greater clinical possibility”. Surely, by now, you are beginning to intuit that this is not only gross oversimplification but also the source of millions of misdiagnoses and failed treatments.

Nonetheless, if you have been carefully following my logic up to this point as we travel up the “anxiety pyramid”, it should be clear that neurochemical imbalances are less a factor of genetics and have nearly everything to do with a cascade of shifts that usually begin with drastic disruption of the microbiome. Every single client I have consulted with anxiety disorder, regardless of the type or intensity, has, to some degree, an altered microbiome and the laboratory results to prove it. This accompanied by a parallel shift in neurotransmitter activity in both the gut and brain.

Consider this: pharmaceuticals such as Xanax (i.e. Alprazolam) achieve their therapeutic effect by binding to benzodiazapine sites on GABA type A receptors, markedly suppressing HPA-axis activity. The drug affects a far greater number of receptors than would naturally occur with GABA produced in the brain. For people with very few problems in the areas detailed above, there are sufficient levels of GABA, via conversion from glutamate, and antioxidant defenses are in good working order. In other words, such people have a natural “pharmacy” in their brain with normal responses to stress. There is an entirely different story for a person with inflammation, oxidative stress, and HPA-axis dysregulation.

GABA neurotransmission is particularly sensitive to oxidative damage, which can result in neuronal damage.31 As described above, oxidative stress can be induced by reactive oxygen species such as superoxide as well as inflammatory cytokines. In the presence of chronic mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation, there will not only be a disruption in neurotransmission, but fewer receptors upon which to act to achieve an inhibitory effect. As the GABA molecule is too large to cross the blood-brain barrier, lower production in the brain will create a chain-reaction resulting in greater vulnerability to excitotoxicity from glutamate. In this scenario, the only way to achieve the same inhibitory effect is to ingest a smaller molecule (such as a benzodiazapine like Xanax) that is able to cross the blood-brain barrier. This approach carries its own long-term risks, as will be discussed in detail below.

Psychological Factors

All of the physiological factors discussed thus far, when combined together, could easily be likened to the materials used to build a ship. If genetics are the blueprint for that ship, then it doesn’t matter how well it is designed if the materials aren’t strong enough to keep out water, as with a compromised gut barrier. If water comes in, then damage will spread throughout the ship (i.e. chronic inflammation), causing its structure to weaken with time. Depending on the state of the vessel, it will either withstand strong tide and winds when they come or, in the case of a ship that has been systemically weakened, be tossed about and possibly sunk by a small storm. This analogy can be perfectly applied to anxiety disorder.

If multiple areas in the physiological portion of the pyramid are in disorder when stress comes along in life, there will be less resilience and higher vulnerability to developing psychological illness or self-deprecating patterns of thought. While it is certainly true that life events such as war, physical abuse, or other acts of violence leave their psychological imprint regardless of a person’s physiobiological constitution, the depth of damage and the long-term adaptation will be of far less impact in those individuals that have adequate “biological resilience”.

That said, let’s examine a few of the psychological factors that can influence the development of an anxiety disorder.

Life traumas

Injury or damage to the human psyche can occur when a person endures severe shock or stress as a result of some external event. Although long-term, psychological distress can be the result, there is usually an event or series of events that are responsible for initiating the problem. Life traumas can be broken down into two basic types:

Trauma Type I: a physical event that creates a long-term psychological impact. This includes birth memories, physical abuse, rape, physical assault of any kind, a serious accident or illness, a medical procedure, being a victim of domestic violence or group violence, enduring natural or man-made disasters, being forcibly displaced, or living through acts of war or terrorism.

Trauma Type II: psychological trauma induced by a shocking, non-physical experience. Such traumas may be a result of using psychedelic drugs, witnessing an act of violence, being abandoned or neglected as a child, witnessing domestic or group violence, being the victim of verbal abuse, or experiencing grief over the death of a loved one.

Regardless of whether the trauma begins as a physical assault to the body or less directly via other senses, the effect in the brain is identical. While physical traumas do result in a more concrete, constant reminder of the original trauma, neurochemical and neurohormonal changes unfold in the same manner, regardless of trauma type.

The earlier the trauma occurs in life, the greater the potential for sensitization of central nervous system circuits. Several preclinical studies have shown that early life traumas are capable of inducing long-term hyperactivation of the HPA-axis. The hypothalamus, in particular, can be programmed at an early age, through repetitive insult, to upregulate secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone which, by the mechanisms discussed above, can result in changes to the expression of inhibitory neurotransmitters like GABA and serotonin.32 Naturally, the possibility for neurochemical imbalance is magnified several times when there are pre-existing issues with the microbiome, inflammation, and oxidative stress.

In the case of post-trauamatic stress disorder, elevated signaling of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 has been observed. As we have already discussed, such cytokines can play a significant role in the modulation of catecholamines (i.e. stimulatory neurotransmitters), high levels of which are strongly linked with anxiety-type reactions.33

I believe the key to understanding and working around life traumas begins with a comprehensive analysis of the physiological factors that contribute to higher vulnerability and lower resilience. As neurochemical and neurohormonal systems come into balance, it becomes considerably easier to weaken negative, toxic neural patterns and allow the brain to form new ones.

Choice of friends and information sources

The people, ideas, and conceptions with which we surround ourselves have a far greater impact on our psychological well-being that many give them credit for. What may not be so obvious is the way in which our choices of friends and information sources are intimately tied to the state of the physiological areas lower in our pyramid. All of the factors we have discussed thus far can have a profound impact on your psychological state of mind in any given moment. We have seen how an altered microbiome can significantly disrupt not only neurochemical balance but also wreak havoc on inflammatory and oxidative processes in the body. When taken together, these changes in our interior, bodily environment can define and shape us psychologically, modulating in no small way the people and ideas we are attracted to.

It should come as no surprise that the earliest influences in our lives, our parents or caretakers, can set the stage for neural imprinting before the brain has even fully developed. According to Albert Bandura’s Social Learning Theory, humans can “learn” anxiety by observing the reactions of those around them. In early life, if a parent or caretaker has a negative or fearful reaction to something in the environment – whether it be something in the news, neighborhood crime, or even the appearance of uninvited visitors – this reaction can be transferred to the child observing it. This transfer can happen even in the pre-verbal years and the end result is a deep, subconscious apprehension that something is dangerous or to be avoided. Such transferance is particularly acute when a parent or caretaker actually suffers from some form of anxiety disorder. In such a case, all the physical and psychological characteristics associated with that caretaker’s disorder are internalized and integrated in the neural circuit, only to surface years later as a result of a stressful circumstance.

As we grow older, we become more and more the confluence of all the physiological and psychological imbalances we have absorbed over time. At every step in life, the people we choose to spend time with will either be a reflection of those imbalances – which will confer a feeling of familiarity and even perverse safety – or we will choose to step outside of our biologically programmed neural network and expose ourselves to new people and potentially uncomfortable but rewarding experiences. Our ability to make this shift has everything to do with the level of physical and psychic discord we are living with at the moment.

Unfortunately, as with many forces in nature, the longer we have been exposed to certain bodily and mental states of being, the harder it is to break free of them. Once physiological anxiety has taken a stronghold, resulting in systemic changes to neurotransmitters and hormones, even positive, potentially life-changing influences may be ignored. They are ignored because they are perceived through the distorted lenses of a body and mind in conflict. In that situation, we find ourselves almost sadistically gravitating toward news sources that confirm or reflect a sense of fundamental anxiety. It never occurs to the victim of anxiety that the people and information sources that have accumulated over the course of many years have become a self-reinforcing paradigm.

To make matters worse, we now live in a time where social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have all but transplanted real, human relationships and interactions. As a result, there is not only a larger volume of information at our disposal but a faster pace, increasing the demand to be wakeful, alert, and “connected”, all of which demand the activation of the sympathetic nervous system. One study even demonstrated that addiction to social media technology could potentially activate the same area of the brain as addictive drugs such as cocaine, especially with regards to the abnormal functioning of the brain’s inhibitory controls.34 Yet another study, conducted at Harvard University, showed that daytime cortisol production was directly proportionate to the size of one’s Facebook network.

But social media isn’t the only potentially stressful source of information. In a national survey conducted by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard School of Public Health, significantly higher levels of anxiety and stress were observed in people that either watch, read, or listen to the news on a daily basis.35 And this should come as no surprise based on what we have discussed to this point.

The people we choose as our friends and the information we exchange with each other is not simply of casual importance to our well-being. It is the re-inforcing mechanism of the brain’s neural network that deepens the groove for thoughts, ideas, conceptions and our overall perception of reality. For this reason, in considering the total pathology of an anxiety disorder, we must not forget to include a stark and potentially unforgiving analysis of our external inputs. If there is to be any change in this area, it may require a sobering reconstruction of lifestyle.

Thought programs

It should be clear, at this point, that the brain’s neural net is formed not only by the state of the body and the signals it is relaying due to varying levels of distress. The net is also comprised of the thought programs we learn as a result of exposure to parents, caretakers, teachers, siblings, friends, and all other potential influences we encounter in the world. And for every thought or memory we return to, that particular circuit is strengthened the more frequently we access it. What initially may begin as a negative or dark comment shared among friends, if contemplated consistently enough, will become a self-reactive pattern. And the more such patterns are ingrained in our neurobiology, the more they play a role in determining our perceptions and reactions to future encounters or events.

As the old saying goes, “practice makes perfect”. Every action and every thought we engage in carries with it a corresponding burst of synaptic transmissions between the brain’s neurons. The longer a certain pair of neurons fires together, the more they “wire together” and the connection between them becomes stronger. Every thought represents a chain of transmissions across the neural network. The more frequently that chain is activated, the more automatic its activation becomes. In this way, through repetition, we learn to perform complex skills almost without thinking. Unfortunately, chronic fear and worry begin to take on a life of their own, also without much say on our part.

Panic attacks, in particular, elicit an extremely acute response in the central nervous system and brain, creating an almost instant imprint in the neural net. For this reason, they can frequently re-surface by doing nothing more than remembering the first incident. And, of course, with each attack, the synaptic pathway through the neural net becomes stronger.

I have met few people that have been able to manipulate firmly imprinted thought programs using sheer will power. The reason is simple: though the neural imprinting has strong reinforcements, the cascade of disruption in purely physiological processes is senior to the program. In other words, if one is to weaken negative circuits and replace them with new, resilient ones, all physiological levels of the pyramid must be fully addressed. Otherwise, it will be an uphill battle fraught with constant setbacks.

Negative self-talk

While it may seem that negative self-talk is a form of thought programming, it is in fact more a reinforcing mechanism for pre-existing programs. Rarely do we find someone stuck in the negative aspects of life without there first being physiological distress and one or another form of firmly ingrained thought patterns. Once neurochemical and neurohormonal imbalances have been established and a sufficient amount of time has elapsed for there to be a strong, negatively-reinforcing neural net, contemplating and voicing negativity becomes natural. Some of the most common self-talk patterns include:

Filtering – this involves neurologically resonating with negative patterns to such a degree that no positive aspects may be perceived. The sun may be shining and friends surrounding you with laughter, but you are tuned into the pain in your stomach, a headache, or perhaps the unpleasant smell of someone standing next to you.

Personalizing – in response to a negative event, you automatically presume that you are at fault in some way. This frequently manifests in social media when an acquaintance doesn’t respond to a message. It is immediately assumed that the friend is deliberately ignoring you because of a silent disagreement or something you have done.

Catastrophizing – you are in constant expectation of the worst possible outcome, regardless of the circumstances. If someone is sick, you will immediately become convinced that you will catch it. Simply walking up a flight of stairs, one might expect that he could fall down and break his leg.

Polarizing – this occurs when there is no “gray area”. It’s either all or nothing, but more than often – nothing. We often see this pattern in people of which much is expected. Regardless of their accomplishments, they are very hard on themselves and perceive their efforts to be completely inconsequential.

The problem with negative self-talk is that it can accumulate in intensity the longer it goes unchecked. What might start as a small setback in life could develop into the perpetual expectation that something bad is just around the corner. In that situation, the self-talk actually becomes a thought program that creates its own circuit in the neural net. With time, this will only re-enforce a sense of hopelessness and anxiety.

Common Solutions and How They Fail

A thorough review of the major physiological and psychological factors in anxiety disorder, as conveyed in the pyramid above, should give us an appreciation for the multi-pronged approach that is required to uncover the root causes. Unfortunately, for as many factors that influence this disorder, there are several times more proposed solutions. And given the consistent rise in pharmaceutical prescriptions worldwide, it should be clear to you that these solutions have not been enjoying widespread success.

A thorough review of the major physiological and psychological factors in anxiety disorder, as conveyed in the pyramid above, should give us an appreciation for the multi-pronged approach that is required to uncover the root causes. Unfortunately, for as many factors that influence this disorder, there are several times more proposed solutions. And given the consistent rise in pharmaceutical prescriptions worldwide, it should be clear to you that these solutions have not been enjoying widespread success.

Ultimately, the most common strategies for dealing with chronic anxiety are, in reality, nothing more than elaborate coping mechanisms. In the field of psychology, coping is defined as “the conscious effort an individual makes to solve personal and interpersonal problems, in order to try to master, minimize or tolerate stress and conflict.” In my opinion, minimizing, tolerating, or even mastering anxiety are at best a form of physical and mental manipulation. If a solution is to be truly effective, it must effectively uproot the need for a coping strategy by completely annihilating the root cause(s).

In order to appreciate the value of the “pyramid of causes” detailed above, it’s important that we discuss in some detail the common coping mechanisms used in contemporary psychology and psychiatry.

Medication

There is not a day that goes by that a psychiatrist or, worse yet, family medical practitioner isn’t prescribing one or another form of pharmaceutical medication for a patient presenting with anxiety disorder. The prescription is already written before the patient can even state his detailed case. Theories abound on why our doctors are not spending more time with their patients to understand their needs. In reality, the reason is simple: the root causes of anxiety have not been sufficiently explained in the medical literature. Few health practitioners have the time, amidst their busy schedules, to sift through the thousands of studies published in the last decade on the human microbiome, mitochondria, immunology, and genetics to derive insights similar to the ones I have been sharing with you in this article.

Let’s make absolutely no mistake about it: pharmaceuticals are not nor will they ever be a valid treatment for anxiety disorder. I make this statement in the face of millions of people that believe they could not function without them and my message to them is simple – the human body is more complex than even the most intelligent medical professional could ever understand. Until you have addressed and thoroughly handled all relevant areas in your particular physiology and psychology, you will never be able to say, with certainty, that your problems could be resolved with options other than medication.

In order to understand why medication is the worst possible option for anxiety, we will need to take a closer look at the 5 basic categories and their inherent pitfalls.

Benzodiazepines

As we discussed in the Neurotransmitter / receptor impairments section of the “anxiety pyramid”, benzodiazapines such as alprazolam, clonazepam, diazepam, and lorazepam bind to benzodiazapine sites on GABA type A receptors, markedly suppressing stress response in the HPA-axis. In this respect, they work far too well and can initially give the impression that the anxiety is under control. Unfortunately, they come with a long laundry list of side effects including dizziness, drowsiness, confusion, blurred vision, weakness, and low blood pressure. Some studies have even shown that chronic use of benzodiazepines can cause immunological disorders.36

In practice, “benzos” should only be prescribed for short-term management of anxiety. The truth is, however, that the majority of users almost always end up in a long-term relationship with them. This leads to a chain of problems, not the least of which is receptor downregulation, including decreased sensitivity to GABA, less binding at receptor sites, degradation of those sites, and eventually – repression of gene expression responsible for the creation of them.37 This is why, with prolonged use, a higher dose of the drug is required to achieve the same effect.

The larger problem with long-term benzo use is that as receptor sites decrease in number and the drug dosage goes higher, the patient is left in an extremely precarious position. Stopping the drug at that point will result in absolutely devastating rebound anxiety, many shades worse than the original problem. In such cases, it is necessary to gradually wean off the benzodiazapine over the course of several months and, at the end of the withdrawal period, the anxiety continues as before treatment.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

Although the exact mechanism of SSRIs is unknown, they are believed to increase extracellular serotonin by blocking its reabsorption, or reuptake, by nerve cells in the brain. The most commonly prescribed SSRIs are italopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline and they all have side effects including insomnia, sexual dysfunction, and weight gain.

The primary problem with this class of drugs is that they focus on only one neurotransmitter – serotonin, without any regard to the deleterious effects on other neurochemicals such as catecholamines (e.g. dopamine and norepinephrine). Whenever concentrations of extracellular serotonin are elevated in the brain, there is a simultaneously antagonistic effect on stimulatory neurotransmitters. While this will produce the desired effect of limiting neuronal excitation in the brain, it could potentially produce other symptoms typically related with low catecholamines such as ADD / ADHD and anhedonia (i.e. an inability to experience pleasure). This problem could easily be exacerbated if there is inadequate intake of zinc, magnesium, iron, or tyrosine-containing protein in the diet.

Another consideration with SSRIs is the danger of prescribing them to an individual that has a primarily “GABA-ergic” anxiety profile with higher levels of extracellular glutamate. The problem could be intensified if there were an overgrowth of beneficial, serotonin-producing microbiota in that person’s gut. In such a case, there would still be some degree of neuronal excitation from glutamate and lack of GABA while levels of serotonin could rise precariously high. I have personally encountered such individuals and some of them have even endured serotonin syndrome after taking an SSRI for several days. Given the symptoms of this syndrome include agitation, sweating, dilated pupils, and diarrhea, an SSRI prescription for anxiety is hardly the answer in such cases.

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs)

In addition to increasing serotonin, this class of medication also raises norepinephrine levels. Norepinephrine (i.e. noradrenaline) is a stimulatory neurotransmitter that mobilizes the brain and body for action. In addition to promoting wakefulness and vigilance, it is also able, in higher concentrations, to cause restlessness and anxiety.

The same risks and side effects with SSRIs apply to SNRIs as well, with the added risk of potentially increasing stress levels as norepinephrine converts to adrenaline via the phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) enzyme. This can be a considerable problem for people that already have some level of HPA-axis dysregulation. Further, neither SSRIs nor SNRIs address an underlying issue with GABA receptor downregulation, which is present in almost every person I see that also has high levels of oxidative stress and inflammation.

Ketamine

Since its discovery in 1962, ketamine has been used primarily as an anesthetic. It produces a trance-like state of sedation via its antagonism of NMDA receptors, which are the primary receptors for the excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate. Ketamine has been further shown to have effects in a wide variety of other areas in the brain, including opioid and dopamine receptors. Its purported dopamine reuptake inhibition in combination with mu-opioid receptor activation have been correlated to its ability to induce euphoria in some individuals.38

Clinical trials using lower doses of ketamine for the treatment of depression and anxiety have shown compelling short-term results. One study showed a significant decrease in anxiety for hospice patients as soon as 3 days into ketamine treatment at 0.5mg/kg per day.39 Though few adverse effects were reported, no study has yet been published that measures the long-term risks of such treatment. The greatest issue with long-term ketamine use, in my mind, is the possibility for abuse in those patients that have issues with dopaminergic signaling, namely low receptor density, altered neurotransmitter binding, and overall low levels of dopamine. In such individuals, neural circuits associating ketamine use with pleasure or reward could be strengthened, creating a dependency. Further, frequent antagonism of the NMDA receptor system can disrupt long-term potentiation in the brain, reducing synaptic plasticity and potentially causing cognitive deficits.

In my opinion, ketamine could be a life-saving treatment for individuals with debilitating, treatment-resistant anxiety or depression, but it is not a long-term strategy for resolving the root causes of such illnesses. Moreover, with single treatments ranging from $400 to $170040 without reimbursement from insurance (in the United States), it can hardly be considered a sustainable treatment option at this time for the majority of people suffering from anxiety disorder.

Psychedelics

This category of substances actually does much more than simply bend perception. They are also known for drastically altering the structure and content of the mind to such a degree that mystical and near-death experiences are often reported. Truly, psychedelics will always be controversial due to their ability to seriously disrupt the ordinary flow of consciousness. In any structured society, regardless of its balance of conservatives and liberals, this sort of disruption can potentially (and has) created chaos in its wake. Nonetheless, there are many clinical precedents both in the past and in contemporary times for the use of psychedelic substances such as LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin in the treatment of mental illness.

At first, one might question how psychedelics could be of use in the treatment of anxiety, since reports of “bad trips” and psychotic breaks are common in the anecdotal literature. A case could easily be made that individuals suffering from anxiety disorder should avoid potent mind-altering substances due to their unpredictable effects. Regardless of such outcomes, numerous studies have shown there to be concrete, non-transient relief from both anxiety and depression when psychedelics are administered in a carefully controlled clinical setting with the proper support and guidance of a mental health professional.

High doses of psilocybin – the active ingredient in “magic mushrooms – have been clinically proven to reduce anxiety in cancer patients. In one study, 80% of the patients continued to enjoy a reduction in anxiety levels as much as 6 months after the study was complete.41 Of that 80%, most of the participants claimed significant improvements in their personal life and relationships.

LSD has also proven effective in its ability to treat anxiety disorders, despite its notorious public history. Clinicians have claimed that it has the unique ability to access repressed or unconscious anxieties and worries, often evoking intense emotional peak experiences. Such cathartic therapy may lead to a change in ability to trust others emotionally, gain greater understanding of difficult life situations, and form new habits and perceptions. In one study, 78% of the participants that experienced such catharsis during LSD therapy achieved a significant reduction in anxiety levels.42

Regardless of such glowing reports in the medical literature, most of the psychedelics used in clinical research to date are of the serotonergic category, exerting their effects via 5-HT2A serotonin receptors in the brain. These receptors are involved in a wide range of functions, not the least of which are learning, mood, motivation, and memory. Activation of the 5-HT2A receptor in the hypothalamus can increase levels of ACTH, the stress hormone produced in the pituitary gland. In individuals with pre-existing neurochemical or neuroendocrine imbalances, agonizing this receptor with psychedelics such as psilocybin or LSD could potentially lead to a stress-induced panic attack – and the repercussions could be long-term, depending on the physical and mental state of the patient.

Further, overactivity at the 5-HT2A receptor has been implicated in the pathology of schizophrenia.43 In individuals that have genetic liabilities for less MAO (monoamine oxidase) inhibition, serotonergic psychedelics could possibly induce a psychotic break as both serotonin and dopamine levels accumulate in the brain.

The fact of the matter is that while there may be a clinical application for the use of psychedelics, especially with regards to cancer patients with high anxiety or the terminally ill, for the majority of other cases, there are simply too many unknowns. Ultimately, a comprehensive analysis of all physiological and psychological factors that contribute to the pathology will, in most cases, yield more sustainable, long-term results without the need for catharsis or potentially fierce disruption of the delicate neural net.

Alcohol

It could be said that in the majority of alcohol abuse cases, there is almost always a component of anxiety. If we look at its mechanism of action, it becomes obvious why ethanol use is common among sufferers of anxiety disorder: it modulates levels of GABA by interacting with GABA type A receptors, similar to benzodiazapines.

But what makes it so beguiling for the anxiety-ridden user is its ability to release dopamine44 and opioids45 in the brain’s reward pathways via NMDA receptor modulation. Dopamine release, in particular, is accomplished by agonizing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the ventral tegmental area of the midbrain (similar to nicotine). So in addition to relaxing the central nervous system, it also transiently but powerfully boosts mood.

The sociological and medical problems with alcohol abuse are well known. What may not be obvious is how repeated use to soften the edge of an anxiety disorder carries with it certain, semi-permanent changes to the neurochemistry in the brain. Of greatest concern is the hyper-sensitivity of GABA neurons to oxidative stress and overactivation. As discussed above, this can result in gradual downregulation of GABA activity in the brain, increasing excitatory neurotransmitter and stress hormone levels over time. Further, with repeated stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in the brain via the ventral tegmental area (VTA) projections, CREB-mediated gene expression will also be downregulated, resulting in a progressively decreasing sense of reward. This eventually requires higher ethanol intake to achieve the same result. In the absence of sufficient reward, it often becomes necessary to seek out drugs that can more intensely activate that pathway.

Regardless of ample warnings from doctors and pharmacies, alcohol is often combined with benzodiazapines, especially in more severe cases of anxiety. This is a most dangerous cocktail that can, with time, drastically alter the GABAergic and dopaminergic pathways in the brain, potentially creating a vicious circle of rebound anxiety and addiction that are extraordinarily difficult to break free from.

Psychotherapy

For reasons stated in great detail in the section, A Unified Perspective on the Causes of Anxiety, the ability of psychotherapy alone to deal with a chronic anxiety disorder is far more limited than the mental health establishment would like to admit. As conveyed in the pyramid above, it is my conviction that most, if not all, cases of anxiety have deep, physiologically-based root causes. Life experiences and environmental influences are often simply the triggers that uncover and exacerbate weaknesses in the body and brain, increasing vulnerability and lowering resilience.

Thousands of techniques exist in the world of psychotherapy for manipulating behavior, thoughts, beliefs, emotions, and compulsions. Few of those techniques consider the areas described above as the potential root causes and fewer yet have proven sustainable in the most severe cases of anxiety disorder.

Take, for example, cognitive-behavioral therapy or “CBT”. The goal of this approach is help the patient become more aware of the thoughts, ideas, and beliefs that influence behavior and emotional adaptation. This may include anything from unconscious coping mechanisms to conscious adaptation, diversion, avoidance, or other mental manipulations.

Exposure therapy takes the approach a step further by either having the patient mimic the physical sensations experienced during an anxiety attack (interoceptive exposure) or by placing him directly into the most feared situation in order to re-train the brain (in vivo exposure). Where interoceptive exposure seeks to eradicate the “fear of fear” or sensation of impending doom, in vivo exposure aims to face the problem head on and, hopefully, learn new adaptations.